Birmingham scientists develop innovative ‘ChemoPatch’ to stop pancreatic cancer returning

Researchers at the University of Birmingham have been awarded £87,000 by our organisation to develop a new device which will deliver chemotherapy directly to tissue left behind after surgery reducing the likelihood of the cancer recurring. In this new study, the researchers will refine their prototype device, named the ChemoPatch, which would be attached to the pancreas delivering chemotherapy more effectively and minimising harmful side effects.

Less than 7 per cent of people with pancreatic cancer survive beyond five years in the UK, making it the deadliest common cancer. Surgery is currently the only potentially curative treatment. Yet, tragically, recurrence of the disease is very likely, recurring in around 75% of patients who have been operated on. Even in patients who do receive chemotherapy after surgery it has been estimated that only around 5% of the administered drug reaches cancer cells. This is thought to be even lower for hard-to-treat cancers like pancreatic cancer, with the rest of the treatment accumulating elsewhere in body, causing side effects like sickness, infections, tiredness, bleeding, and hair loss.

The project, headed by Dr Christopher McConville, Associate Professor in Pharmaceutics, Formulation and Drug Delivery, received a Research Innovation Fund award from our charity in a bid to improve survival following surgery. Pancreatic cancer recurrence is high due to microscopic cancer cells, undetectable to the naked eye, being left behind after surgery. Around 50% of recurrences happen within the pancreas itself.

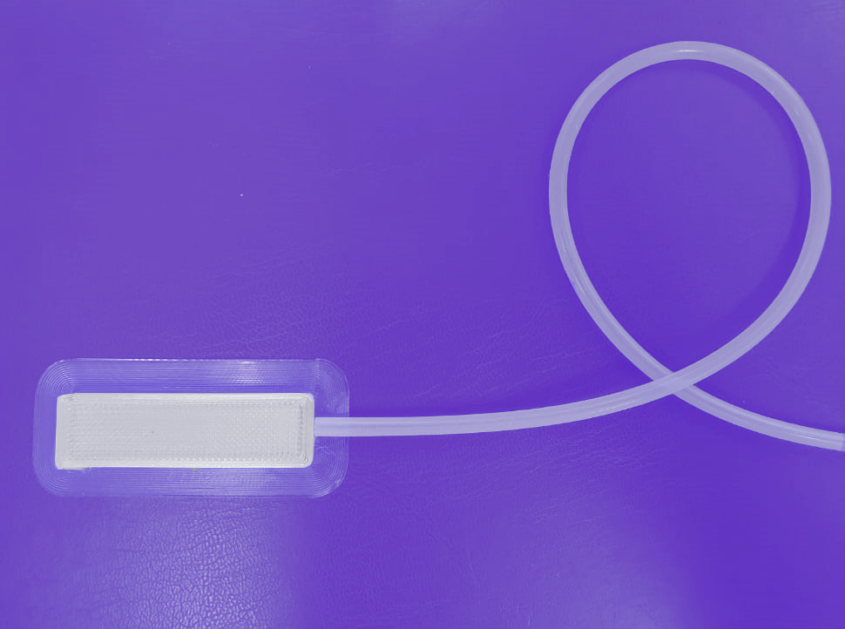

The ChemoPatch device

The ChemoPatch device would be implanted during surgery and used to administer chemotherapy directly to the remaining tissue, specially targeting any rogue cancer cells. The chemotherapy drug would be loaded into the device via a hollow silicone tube and then released slowly into the body over a period of seven days.

Researchers hope delivering chemotherapy this way will greatly decrease the likelihood of recurrence, improving survival and quality of life due to reduced symptoms. Administering chemotherapy locally will mean lower levels of the drug can be used, allowing all patients to be treated with the more effective, but more physically demanding, FOLFIRINOX.

The most common surgery for pancreatic cancer – a Whipple’s procedure – can take six to 12 hours and involve removing the head of the pancreas, as well as part of the small intestine, gallbladder and sometimes part of the stomach. Recovery for many patients can be slow, affecting their ability to tolerate chemotherapy. Receiving the drug after the operation has been proven to increase survival but up to half of patients are not given it, in part due to many patients are not being well enough.

Birmingham resident, Alice 64, knows exactly how gruelling chemotherapy can be. She was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer after becoming unwell on a holiday in July 2023. Initially thought to be pancreatitis, scans later showed she had a lump on her pancreas.

Alice said: “I was absolutely stunned. I couldn’t possibly have pancreatic cancer – my husband died of cancer; my daughter had already lost her dad as a result we had done cancer. I was fit and healthy. How could I have it as well?”

Alice started chemotherapy three weeks after seeing the oncologist The tumour looked to be impacting a significant artery and doctors hoped chemotherapy would pull it away so she could have surgery.

Alice said: “My surgeon had told me nutrition, fitness and psychology were really important. Day and night I would be repeating the mantra; ‘this treatment is working for me. This is getting me to surgery, I’m going to have surgery.’ Chemotherapy is such an archaic form of pouring toxins into your body, but I knew I needed it if I was going to survive this.”

The seven cycles of chemotherapy were extremely effective, and Alice was able to have surgery. Alice was discharged home on Mother’s Day and began building up her strength for ‘mop-up chemo’. chemotherapy

Alice said: “Knowing there are people out there who can have had surgery but then are too unwell for vital mop-up chemotherapy is an absolute shock. I never even considered that I would not being able to finish my treatment plan. Having a device which could make chemotherapy easier to take would make the world of difference – more people could survive this.”

“I call them rounds of chemotherapy as it does feel like you are in a boxing ring at times. I would have loved the opportunity to have a device like this. If you can minimise the intensity and variety of the side effects that would make such a difference, but this could also reduce the time spent in a hospital and time going to-and-from appointments, and that would be life changing.”

Alice Rees

Researchers will build on the prototype they’ve already produced and design an implantable device that is suitable for patients, taking into consideration size, flexibility, and shape. They will also determine how best to attach the ChemoPatch to ensure it is secure, experimenting with stitching and surgical glue. If the project is a success, researchers plan to take the device forward for further testing in clinical trials.

Professor Christopher McConville, who is now Professor of Biomedical Innovation at Ulster University, said: “We have good drugs, we just choose to give them to patients in an inefficient way by injecting them into the bloodstream or swallowing them as a tablet. When we test cancer drugs on cells in the lab or in mice they show a lot of promise, however, this is rarely replicated in patients due to not enough drug getting to the cancerous tissue to work, plus we are limited in how much we can give due to their side effects. This is particularly true for hard-to-treat cancers. Using an approach like ChemoPatch will allow us to deliver small, but effective, doses of the drugs directly to the cancerous tissue, improving their clinical performance by increasing efficacy while reducing toxicity”

"Using an approach like ChemoPatch will allow us to deliver small, but effective, doses of the drugs directly to the cancerous tissue, improving their clinical performance by increasing efficacy while reducing toxicity"

Dr Chris MacDonald, Head of Research at Pancreatic Cancer UK said: “We desperately need more treatment options for pancreatic cancer. Surgery is currently the only potentially curative treatment, however tragically in 75% of cases the cancer reoccurs within a year. It’s vital we stop this from happening.

“This innovative new technique offers the opportunity to much more quickly deliver a high dose of post-operative chemotherapy to the right place, whilst also minimising side-effects. If successful, this research could have a really positive impact for patients and, crucially, help improve survival for the deadliest common cancer.”